interview: Mark Renner

Mark Renner is a visual artist and musician. Born in Baltimore but having grown up in the city’s outlying countryside, his work is infused with the stillness and solitude of rural living and countless hours spent quietly observing. His first solo exhibition, The Lost Years, was displayed in Baltimore in 1985, followed by a 1989 exhibition, Creatures That Die In A Season. At this time, Renner also recorded two albums, 1986's All Walks of This Life and 1988's Painter's Joy. The albums paired elegant synth pop with ambient, almost baroque instrumentals in a way that feels both of its time and utterly timeless. The albums did not make much impact, and Renner fell off the pop culture radar—if he’d been on it in the first place. In the following three decades, he settled into family life; moved to Fort Worth, Texas; and continued to make art and music, more or less in obscurity. Then, in 2018, the Brooklyn-based label RVNG, having discovered his debut album, contacted him with interest in reissuing his music. The resulting collection, Few Traces, thrust Renner unexpectedly into the spotlight. The album received positive critical attention across the globe, introducing many to an artist few outside Baltimore had previously heard. This is how we discovered him, and we were thrilled to learn he lived only a few hours away. We met with Renner at Fort Worth’s Kimbell Museum to discuss his life and work, his friendship with the late Stuart Adamson, and his forthcoming album, Seaworthy Vessels Are In Short Supply.

I’ve read that you consider yourself first and foremost a visual artist. How do you feel now that your music has started receiving renewed attention?

MR: It was a shock, and I do owe a great deal of debt and service to Matt [Werth] from RVNG, who sought me out. I think he’s someone that, as a label owner, it’s not a business for him, it’s really a passion. He’s sought out several different acts that he told me about that he had to dig out their back catalog. When he first contacted me, I wasn’t sure of his level of interest—I mean, it's very flattering for him to tell me the story of how he came across my first album crate-digging, but I wasn’t sure. He told me what he would like to do, and I was really, really honored by the sweat he put into it, the package. It’s been very interesting, and because of their global reach I’ve been contacted from people in Oslo, and in England, in Poland—all over the world, really. And people have really enjoyed the recordings. In a way, it’s like being congratulated for something you did in high school because it was so long ago.

I think the highest musical compliment I was ever paid, there was a woman I knew in Baltimore, she had I think my second or third recordings. Her dog died, and she said, “I took your CDs to the park after my dog died. It really brought me great comfort just listening to them.” That’s a great honor that people would find anything at all worthwhile in those. To think that, in the moment they were recorded, it was just minimal equipment, on a table in a very small house I was renting at the time, with a view to do nothing more than create a sound installation for an exhibition. And as I became more involved in bands, eventually I was put on a recording. But I guess to directly answer your question, I was very surprised and truly, truly honored.

Most of the music on RVNG’s compilation Few Traces was culled from your 1986 album All Walks of This Life. When I first heard it, I was reminded immediately of one of my favorite artists, Felt, and your music is similar in the way you combine elegiac guitar pop and elegant, almost baroque instrumentals. But the pop songs are something of an anomaly in your catalog, and it’s my understanding that you recorded those songs with Stuart Adamson of Big Country, is that right?

MR: Somehow that got into a press release, I think. We were due to record that... I was a friend of Stuart’s. In the late ’70s I started writing him, and we corresponded. I was in England and Scotland and he invited me to come up and stay with him in Dunfermline, he and his wife Sandra. He really extended himself, and he wanted to help me with music; he was very enthusiastic. If you know the song “It Might Have Been”—it was called “Saints and Sages” on the Few Traces compilation—Big Country would use that recording to open on their tour when they were getting ready to come up on stage. So it was really an honor that he would promote it like that. Of course, it wasn’t available—I think he was the only one to have a cassette copy at that time. So he recommended a studio he worked in, in Edinburgh.

At the time, you could book studio time and fly over to the UK for close to what you would pay in Baltimore for a solid studio. So we had planned with a group I was working with at the time called The Favorite Game, after the Leonard Cohen novel—we had planned to record in Edinburgh with someone that Stuart had recommended. But as Big Country’s first single took off, Stuart became entangled with commitments and wasn’t able to produce. We had booked into Castle Sound in Edinburgh, which was a studio run and engineered by Calum Malcolm, who did the Blue Nile records, if you know them. At the last minute Calum called and said, “I’ve got to cancel.” And, actually, I had dinner with PJ Moore from The Blue Nile back in the fall, and I was telling him this story about how we got bumped out, and he said, “Yeah, it was probably us.” He said they just owned the studio at the time, they were spending so many hours recording. We wound up recording in a small studio in London, Alvic Studios.

Had you been to Scotland before?

MR: Yeah, I’d been there.

Are you Scottish?

MR: I have a very fragmented heritage. I’m part: I have Scottish blood, I have Irish blood and I think Scandinavian blood. The name Renner is Austrian... I haven’t traced my genealogy. I read an article this week that they’re less reliable than they claim to be, the DNA traces. But yeah, I do have Scottish blood.

Do you have relatives living there?

MR: I used to. I have a lot of friends there, good friends, and have over the past. Our relationship has kind of drifted apart, but do you know the painter Peter Howson? Scottish painter... I was friends with him for quite a while. For the recording I just completed in the last year, Seaworthy Vessels are in Short Supply, I did some work with a musician/ composer named Malcolm Lindsay. He produces music for film, he’s a classical composer. I don’t know if you saw Wyeth, the PBS documentary that was on Andrew Wyeth—I actually I think it was on the whole Wyeth family—but he did that. He’s worked with David Byrne, and he’s worked with some folk artists he’s produced in the UK. I was introduced to him years ago and really loved his work and was always hoping for the opportunity to work with him, and we were able to do that. I’ve gone every year since I’ve met Stuart. I usually spend anywhere from a couple weeks to a month there. Glasgow is my second home.

So you wrote to Stuart? How did you find his contact?

MR: I think it was probably anomalous that somebody from America had even gotten an early Skids record—he was with the Skids then. Days in Europa at the time was really just an astounding album for me. They were an unusual group in that Stuart’s guitar playing was very melodic, and Richard Jobson’s lyrics were not the normal things that most of the punk groups of that era were writing about—he was quoting from Wilfred Owen and the war poets, Rupert Brooke and people like that. It was interesting, some of the themes that they were bringing into music. It was a very interesting production, too.

A friend had given me the first seven-inch of the Skids’ called Charles—that wasn’t thematically too heavy, but it was pretty interesting, a little bit more than three chords. I worked for three or four independent record chains at the time, and eventually I worked for a musical wholesaler. I wrote in care of Virgin—they were signed to Virgin, and I got a really lovely reply. We started corresponding back and forth, and it evolved. I kind of lost track with him… [Big Country] just had this meteoric rise, and it was very hard to keep in touch. They have so many clingers on when they get that big, and you don’t want to be an additional one. I talked to someone a couple years ago that knew Stuart around that time, too, and he said he felt the exact same way. He was a gentleman, a guy with a heart as big as Scotland, and it’s really tragic to think he died alone in a hotel room. It’s pretty sad.

The Skids and Big Country had very distinct sounds, and very distinct from yours, but some of their lyrical themes are similar: a reverence for nature, the dignity of man. I was wondering if they were a lyrical influence on you, or if that was already there?

MR: It’s been so many years, it’s hard to say what I was thinking about. “Saints and Sages” was probably Kahlil Gibran—something like that, that you caught in high school. But I would say it was inspirational in the sense that your three- or four-minute song didn’t have to be something radio palpable, or your subject matter didn’t necessarily have to be love, so I guess in that sense it was inspirational. But I think it's fair to make those analogies and those comparisons because Stuart just loved Scotland, loved the place he came from. He’s a great ambassador for Dunfermline, the city that he lived in. I grew up in a rural environment surrounded by farms and fields, and I think that may have seeped through in my earlier stuff.

In your later stuff, too, I would say. [laughing]

MR: Probably still does, yeah.

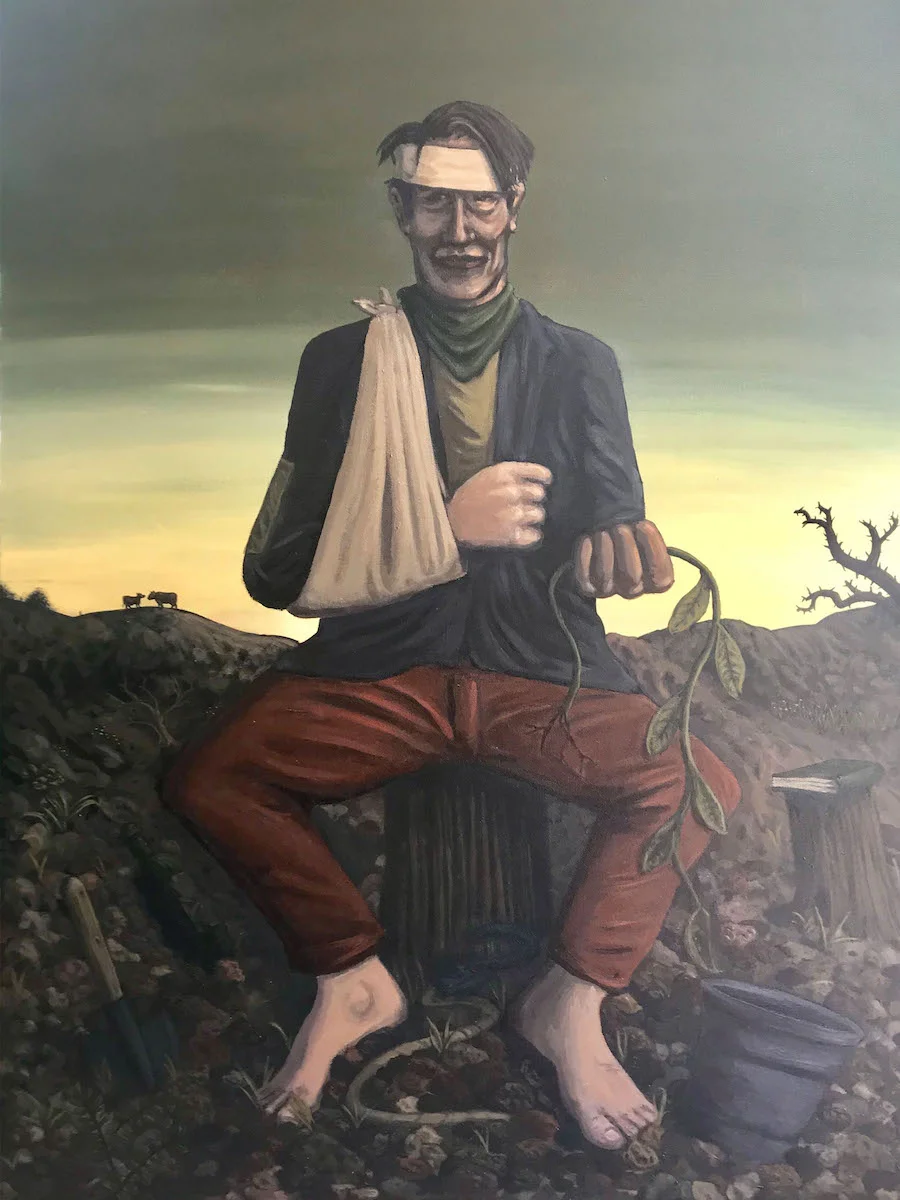

The Arcadian

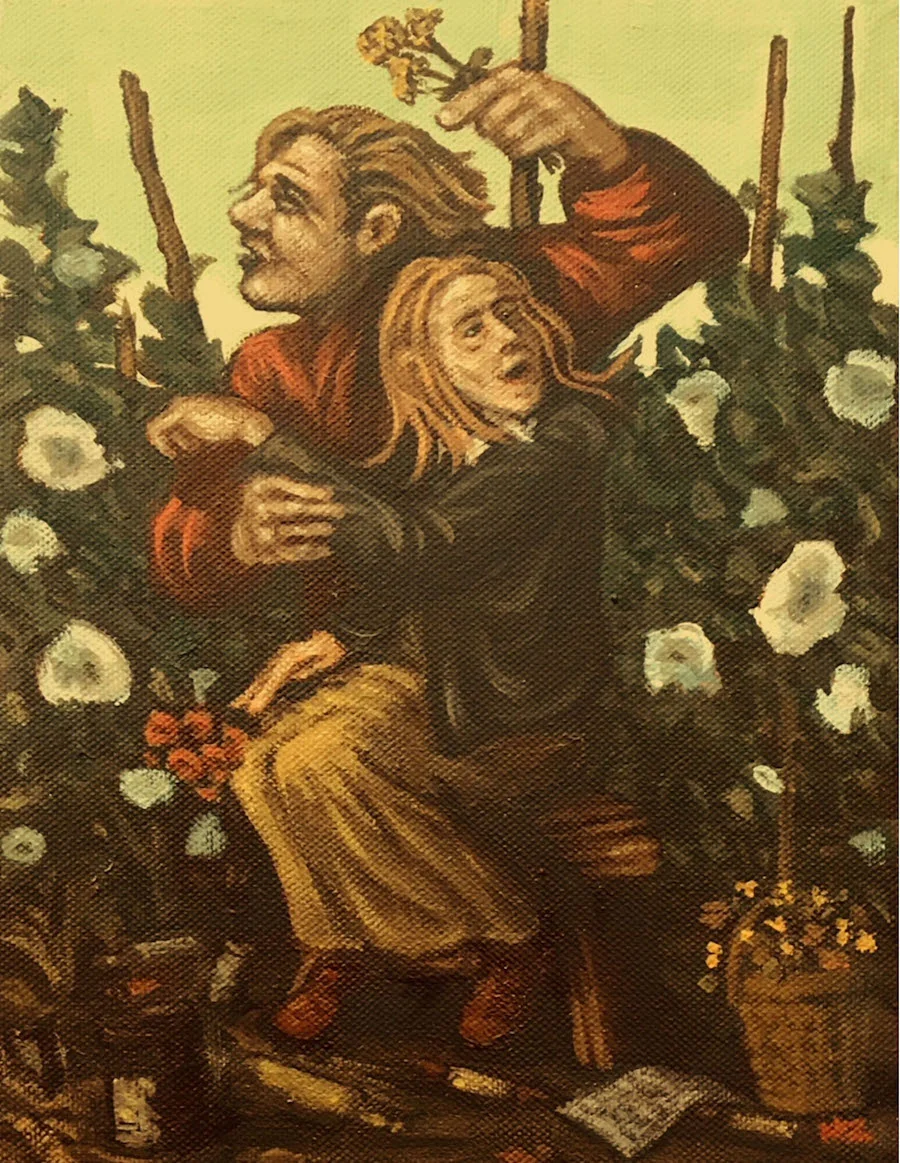

I would like to talk more about the imagery of fields and farmers, that sort of simple agrarian lifestyle. You see it clearly in your paintings and your prints, but I think you curate it in your music as well, in the themes you sing about. What attracts you to this romanticized vision?

MR: Well, I don’t try to create an idol of it, but you’re normally a composite of the things you encounter in your youth. I think that for many, many years I resented it. It’s like Mark Twain or something—you can’t wait to leave, and then when you leave you realize how much you love it and can’t wait to get back, and spend a lot of time trying to return to it. I think I resented the isolation. I’m solitary by nature, but I think the amount of time I spent alone… It’s certainly something that stays with you. As a writer, you try not to hang on the clichés, you try to find a different way, poetically, to express that, but it does get hard sometimes to express what it was like growing up in that condition, and the way it was once was: a very pristine area teeming with pheasant and deer and rabbit and all sorts of wildlife when I lived there.

Were you born on the farm?

MR: No. I was born in sweet suburbia, but my dad moved at a young age. My dad kind of burned in company—he avoided contact. I don’t think he was necessarily an introvert, and I wouldn’t consider him completely misanthropic, but when he got his farm it was like the greatest thing that happened to him. He found this dilapidated farm, I think he purchased it for 14 grand, with 12 acres surrounded by all these other farms back in the mid ’60s, and moved in there. The first night we were there my mother cried. The house was this old Victorian farmhouse, and she cried.

I was one of six children: it was me and my older brother, initially, and then there were four boys by that time we moved to the farm. My sister was born on the farm and my youngest brother was born there. It was a very different way of life.

Did you work the farm?

MR: I always called it more of a gentleman’s farm. My father had enough cattle or livestock on it to use it as a tax shelter, but he never really [used it]. He talked about doing everything from evergreen trees to growing alfalfa. One time, I tried to get him to raise sheep and goats, and he wasn’t really interested in that.

My father retired when he was 42—he had worked for a big corporation, and he had just had enough. I think it was important to him to have that farm. He always stored hay for horses and other people and the surrounding farms—he would store hay for them, and straw in his barn, but it wasn’t ever really a working farm. But about 25-30 feet from my bedroom window was a cow pasture that had cows on one side and thick woods on the other side, and flanked at the bottom of the property there was Piney Run, a stream that kind of weaved its way through Carroll County and Baltimore County. It was idyllic. I don’t think I’m overstating or over-romanticizing—it really was a beautiful area to grow up in.

When did you begin painting and playing music?

MR: I can remember drawing in kindergarten—there was one guy that sat next to my left and we were always very competitive about it. So I know I was at least drawing by the time I was in kindergarten because I remember showing him how to draw certain things. As for music, my mother played guitar. I think she knew two songs: “500 Miles,” a folk song—

Not the Proclaimers’ version?

MR: No, no. [laughing] And she knew, I think it was “Kumbaya,” something kind of cheesy. She had an interest in music—she liked Simon and Garfunkel. I remember the Simon and Garfunkel album Bridge Over Troubled Water. So I probably would have had her guitar before I was 10, but back then you had to tune it with a pitch pipe—it was before tuners were readily available. There was a guy up the street that played bluegrass, and I remember carrying the guitar up the street so he would get it tuned for me. I may have known two or three chords, but it took a while to build up calluses and put those things together. I would say before 10 I picked up the guitar, but then I started thinking about writing music much more in high school. I had a friend in high school, we’d play guitar together. I had this wonderful music teacher, the course I think was called Music Studio, and he allowed all the guys that were advanced in this guitar course he was teaching to go off in the side room during the class hours and just play together. I learned a few more chords form the guys I was playing with, we would just sit in there for an hour, so then I really started being able to get something out of the instrument.

I graduated high school in 1977— that was probably the apex of punk. Hearing the first Clash album, and Nevermind the Bollocks, and eventually the Skids, and… what else were big albums at the time? Magazine, a group from Manchester. I had a good friend, the guy I would play guitar with in high school, eventually he played guitar and keyboards in The Favorite Game. We stayed together—we were always digging and finding new musical discoveries to inspire one another. It was an interesting time, then, for music, with so many independent releases coming from the UK, and from the US: Television—early Television, Tom Verlaine. Seminal recordings. At the time, they were inspirational.

This must be when you moved to Baltimore?

MR: I left the farm and I kind of drifted around. I had a studio, a painting studio down near Johns Hopkins at one point. Then I moved to East Baltimore, into a small row house there. Then I just kind of moved around within the East Baltimore community until I moved to Texas.

You weren’t attending school or anything?

MR: I did. I started going to Towson—it was called Towson State College at the time. I really became disenchanted with a lot of the instructors I had. I was a figurative painter, and interested in figurative work, and they were kind of leading the way to more conceptual things, and colorists. I respected that proclivity, but they were denouncing and really, really hard on figurative painters. I had a similar friend that I went to high school with that experienced the same thing at this college, so it was redeeming to find out I wasn’t the only one.

You lived for a long time in Baltimore. Tell me about the scene there, your music and art. I know I’m not novel in saying this, but it seems particularly incongruous with the city.

MR: Yeah, you had your spots in any big city at the time, when the punk and post-punk scene was happening. You had your dive bars that, probably out of a lack of anything else to draw anybody in, they would open their doors to bands like that. We had in Baltimore a club called the Marble Bar, which was in the basement of the Congress Hotel, and it was a pretty sleazy and seedy place at the time. You wanted to take a bath after you left, but they were very accommodating when punk happened. I think they had Iggy Pop there, they had Psychedelic Furs there. We actually opened for Flock of Seagulls there—I don’t like to speak bad of them, but I think they were very resentful. They were happening on MTV at the time, and I think they had booked the tour before they had gotten big, and so it was a very small club for them. We were trying to be able to do a sound check and they wouldn’t even let us on the stage, the keyboard player was sitting there on the stage playing Simple Minds covers, just looking at us.

So we had the Marble Bar, and there was a club called the Parrot Club close to the Maryland institute College of Art. We drew from that—between my first and second band, we kind of created a scene there, and some of the other independent groups started playing there. The guy kept on asking us back; sometimes we were playing there two and three times a week, which was really unusual for a band playing all originals. It was strange.

There was probably one of the best music record shops in the world at the time, it was a shop called Music Machine. A lot of musicians hung out there, and guys that played in bands, and it’s where a lot of people bought their music. That was just in the outlying county of Baltimore. The guy there used to actually take trips to the UK on buying sprees and come back with rare stuff that people couldn’t find in the US. They would read about in the New Musical Express and they couldn’t get it. He would go over on buying trips and get all these releases and bring them back. It was a great shop and it was kind of a scene—a lot of people congregated around that store, a lot of people that really knew what was going on in the UK and independently here at the time.

It seems that you were part of a good community and supported by like-minded musicians. What about your visual art? Did you find it to be a nurturing scene in that regard?

MR: When I moved to Baltimore there was, in Fell’s Point, a member’s gallery, and my first big exhibition was there. Essentially, the artist would rent the gallery and then you kept the proceeds minus a nominal commission—I think it was only 10 percent at the time, they would take 10 percent to go to the gallery. The Lost Years cassette, which included most of the material that wound up on All Walks of This Life, was recorded for an installation there. That was even before CD Walkmans, there were cassette Walkmans, and the idea was that you provide a cassette and bring along your Walkman and you can walk around the gallery and look at the paintings that were in there and the drawings while you’re listening to the short pieces.

That’s a cool idea.

MR: I think somebody asked me one time, “Why are your pieces so short on that?” And that’s mainly the reason, so people didn’t have to linger in front of a painting. Those eventually became the All Walks of This Life instrumentals.

Each painting would correlate to a specific song?

MR: Yeah. I can’t remember if the titles were exact or not, but I know some of the titles were the same.

What was the reaction to this exhibit, and to your albums when they were released?

MR: I don’t remember there being much of one. I sold a few paintings, and as I told you before, that has always been a great honor to have somebody that would invest in your work and want to look at it every day. I made a contact with someone that worked for public television at the time, and he was interested in the instrumental work. At the time I had great interest in producing soundtracks and working in film in some way, or maybe providing background music for television or documentaries or something like that. I was really hopeful—we corresponded back and forth, and then he rather abruptly said, “Yeah, I don’t think this is what I need right now.” I think it probably had to do with the fact that all that stuff was recorded on four-track, and I think to translate it to television there was a lot of hiss in it, and he probably needed more hygienic recording than what I had on cassette.

That kind of bottomed out, but it was encouraging—the interest, at least. I don’t really look at it as a victory or defeat; it was an encouragement.

Throughout the years there were other galleries in Fell’s Point that I exhibited at while I was in Baltimore. There was one in Canton that is no longer there—a guy named Joe Lemastra had a framing business and a gallery there, and I had a book that came out, and I did an exhibition to coincide with the book. That sold very well—he originally gave me two weeks, and I wound up staying for two or three months in that gallery. That was received very well. I think the good thing about prints is that sometimes people want something smaller that they can take with them. I have always strived to make my work as affordable as possible. I go around and around with gallery owners about that—you try to make your work affordable. Somebody stands before your painting and says, Gee, I wish I could afford that, and you want them to have it because it means something to them.

But that was a very rewarding exhibition because a lot of the work moved and because people seemed to really enjoy the work. Some of the work was actually inspired by some of the neighborhoods in Baltimore. The exhibition was called Sweeping the Floors in the Temple of Life.

I’m surprised to hear that you were interested in creating music for television or film, because your music seems both closely attached to your own visual work and divorced from modern technology, in a way. Especially your more recent music—it’s very high fidelity, and of course it’s electronic, but it seems meant to be enjoyed in nature and to exist outside of contemporary forms of entertainment.

MR: Yeah. I guess it really would depend on the production. I like the amalgamation of the pastoral and electronic; I like that mix. I do like to use strings. I enjoy naked piano, although I’m not so great a pianist that I could play solo—I mean, I could record something and fake something in the studio, but I freeze up when I play live.

“I think the highest musical compliment I was ever paid, there was a woman I knew in Baltimore, she had I think my second or third recordings. Her dog died, and she said, “I took your CDs to the park after my dog died. It really brought me great comfort just listening to them.” ”

I confess, I have not heard Painter’s Joy, but I’ve read that you were unhappy with it, and that the recording process was rushed. Did that turn you off from trying to continue to release albums with labels and kind of work in the world of pop music?

MR: Probably not. I mean, I was 28 years old at the time, and my second son was just born, and I’m kind of looking at the pragmatic sense of chasing something with this completely indefinite and tenuous [nature], and with someone really depending on you at home. Some people are able to do that, and do that with a balance, but normally it’s really the child that suffers.

The rushed part of it was, if I didn’t give them what they wanted, I probably would have missed the opportunity to have the recordings released all together. The A&R guy for the label was a lovely, lovely guy—I just wrote him a couple weeks ago, named Jeffrey Platt. Much like Matt [from RVNG], he really pursued me and encouraged me, and it sounded like it was going to happen for a while, and then it wasn’t going to happen because he was affiliated with a rock label and they weren’t doing anything really experimental or out of the ordinary there. But he pursued me.

I felt that I would’ve liked to work with the material again. The great thing about the affordability of the technology that’s available now is that I’m working on a remaster of that album this year, and I can re-address some of the mastering problems. I wouldn’t attempt to re-record it because I think it stands as a sort of archaeological piece in itself, but to re-record some of the songs as bonus extras and probably make it the way I would want it, tweak this or that. We are going to remaster the record, so maybe I’ll make it a little bit better listen so you can balance some of the weaker parts audible in the original .

It’s a complex situation of getting everything ready because it went from a four-track cassette player to an eight-track studio. Some of that, when you’re mixing—if you had four tracks, you would record three of the tracks, and then you had one empty track. You would mix those three tracks down to the empty track, and then you would have three clean ones to record more on. A lot of that stuff was layer upon layer upon layer upon layer… and then after a while you had the tape hiss, and it got kind of degenerative. So that part was rushed, and I had a few other recordings at the time that were written and just rough demoed with a cassette player, but they needed re-recording at the time. For that part, I would have liked to have more time, but I had no bad feelings about the experience other than that I think the songs, at least two or three, had more potential than you can hear on the recording.

I look forward to hearing the remastered version. You’ve said that, especially some of your earlier music, you would write it and it was meant to be listened to in accompaniment to your visual art at gallery exhibitions. How do you expect audiences to interact with your music these days?

MR: It would be rewarding to me if it inspires somebody to think or to really listen intently to it, if for nothing else than the amount of time you agonize over lyrics and you agonize over subtle details. I understand that different people—my wife, for example, listens to music completely different than I do. I usually, not to a damaging sense, but I will turn the volume up to hear the little nuances in the production, things you can’t hear at a lower volume. She can listen at a lower volume and it’s all she needs. I usually like the whole package—if something is really good musically and the lyrics aren’t good, it’ll probably lose me after a while.

But it would be nice if someone could stick with it and give it a listen. I guess probably what anybody would want is a fair listen to the recording. Because for the people that are damaged by bad reviews in the press or something, when somebody dismisses the recording—I forget the name of the band, but I remember a one-sentence record review back in the punk days that said, “As repulsive as the name implies.” That was the whole album review for the album.

I would think the band would take that as a compliment. It’s probably what they were going for. [laughing]

MR: I would hope that people would consider it, but at the same time I understand that it’s not for everyone.

When did you move from Baltimore?

MR: Nine… Almost 10 years ago.

And that’s when you moved here?

MR: Yeah, that’s when I moved to Fort Worth. In a strange roundabout way I met my wife in Ethiopia, doing missionary work in an HIV project. She was a med student, and she attended a church in Brooklyn that was partnered to my church in Baltimore, and we both were on visiting teams. I didn’t actually meet her until we got to Addis [Ababa]. We teamed up and did a lot of home visitations together. I really admired her; she’s exceptionally smart. We laughed a lot together in our first week. We just had a wonderfully, wonderfully warm chemistry in our whole team that week. My memories of meeting her there were truly pleasant.

We were there for two weeks together, and then we talked about the possibility—I don’t know if we tried to talk each other out of it at first because of living so far apart, but she was nearing the end of medical school and getting ready to begin her residency here, and she always chides me that if I had let her know that I was interested in pursuing a relationship that she would have applied to match at a university in Baltimore. I think the University of Maryland medical system was on her radar, and maybe Johns Hopkins. But that didn’t happen, so I started visiting here.

It was unusual. Before you get to Texas you imagine it differently. I remember when we were in elementary school we were visited by some children from Russia. Our question to them was, What did you expect to see when you came to America? They said they thought everybody wore a cowboy hat and stepped out of a stretch limo with horns on the front. I certainly did not know what to expect, but I guess it wasn’t what I expected.

This was in the ’90s, or 2000s?

MR: This was in the 2000s. It would have been 2008.

You were working in Ethiopia as a humanitarian worker? But you don’t have a background in medicine or anything like that.

MR: No, my wife obviously was [doing] the medical part. I worked as an art teacher, laborer and clinic coordinator. I went not knowing what I was going to be doing, contributing to a team, but my niche became working with children. My father-in-law calls me the Pied Piper because for some reason children are attracted to me. I’m interested to see, as I get older or grayer, if that will be the same. But I still relate well with the children in Addis, and they seem to relate well to me. That has been my sort of niche to the project.

I’ve gone back, 12 more visits—I was just there in February. We had a period of two years, because of the political unrest there, where we weren’t able to return. I don’t think I will ever be removed from this project completely—I have a lot of good Ethiopian friends there. I’m very much in touch with their day-to-day struggles. A lot of the guys that are nurses and work in the project, they’re just like a lot of the other citizens in Addis,economically they’re just trying to keep their heads above water. Staggering inflation rates, and a lot of things are happening in Ethiopia. As governments go in Africa, it’s probably one of the more stable but, at times, it can be a dictatorship masquerading as a democracy. They have a new prime minister who has really buoyed the optimism there, including among my friends who were always very, very skeptical of the leadership. It’s like an old-boy network that they have to dismantle, and things like tribal favoritism and things like that.

That never happens here. [laughing] This is just volunteer work right?

MR: Yeah, it’s all volunteer.

What inspired you to get involved in this?

MR: Well, my pastor in Baltimore’s brother was there as a photographer for Reuters in Africa, and he went to Ethiopia in the ’80s—I don’t know how close it was to “Do They Know It’s Christmas,” the big fundraiser for Ethiopia—but he was there when people were keeling over, dying in the streets, and he really felt that he could not leave and ignore what he saw. He had been a missionary with a sending agency for many years in northern Africa, and he felt that he had to do something in Ethiopia.

When they started out, they were not completely penniless, but they had very little operating funds. They were more or less helping people die with dignity; going and visiting people in their houses and holding them and trying to feed them. That was before the ARV drugs were available, so there was nothing available to assist them medically and very little available to bring comfort to those infected.

The program grew with the advent of ARV drugs, and they were initially able to afford to get two families on them, one woman and one little boy—they could only afford two. The results were miraculous, not quite overnight but an immediate increase in stamina and energy and eventually a return to normalcy, or as close as you can get there. When the PEPFAR funds became available [in 2003] it made an immense impact in HIV/ Aids treatment. I always tell people Ethiopia is one of the rare places you can go where they speak highly of George W. Bush because of this. They knew it was a life or death issue, and they are very thankful toward America and Americans that come and visit.

Honey in a Salty Sea

It seems like you took a pretty large break from music, from 1990 to the mid-2000s. Is that true?

MR: Yeah. It was probably to concentrate more on visual work, and also working a job at UPS—I went from working part-time there to working full-time. I think I was much more visually oriented [then]—I exhibited in Idaho and New York and New Jersey during that time, different places around the country, invitationals and things like that. I did stay active; I always stayed active with the visual work..

That was probably a period just before the DAW visual-audio workstations were available on the PC. I had a porta-studio, but I really wasn’t going much. I just didn’t have the time, with the work at UPS, to put into it. Somebody sold me on FL Studio—it was called Fruity Loops at the time—somebody gave me a demo version of 3. I’ve been with them ever since. It’s like an old car that you drive, you’re just so used to it.

You still use it?

MR: Yeah.

I didn’t even know it was still around. That’s wild.

MR: Well, they kind of refined their name to FL studio to let people know it’s more than just a loop-based program. They’re up to version 20 now. I have version 20, 20.5, whatever they’re on. I still record on that. You can record into the program now; a lot of the demoing I did for the album Seaworthy Vessels that I just finished was all demoed at home on Fruity Loops, and all the tracks are saved as .wav files, and then I take them into a bigger studio.

The songs I recorded with Malcolm in Glasgow, he just ripped them up and started all over again. He did some really interesting arrangements. I’ve never worked in that capacity—usually working with someone, the few times I have, they augment what you’ve done, and he sort of tore it down and started anew, and really to an interesting effect. The title song on Seaworthy was a very chaotic mix and I couldn’t figure out what to do, I had so many tracks competing, and he said, “see what you think,” and he stripped it down. It’s more of an acoustic song now, an acoustic arrangement.

Do you often collaborate with people when you create your music?

MR: I’m in a situation with a guy who will be playing in the live band who’s played drums for us and some guitar. He’s very talented, very gifted, and he must be the best kept secret in Fort Worth. I don’t even know if I want to mention his name. His ability as an engineer—he’s a fantastic engineer. He just loves music, he works another job that kind of taxes him, but he’s always got something left in the tank for music. I began the album, recording out of a horse trailer about forty minutes north of here.

It was interesting because I always enjoy entering a different work relationship, [with] a different engineer. This studio where I’m recording now—Efren Solorio is the engineer’s name—he’s just a wonderful human being. Very talented; he can play drums, some keys, and guitar. Not unlike my experience recording in Baltimore with John Grant at Secret Sound—he was that same type of engineer. He’s very gifted as a musician. Maybe not as much as a writer, but if you told him what you wanted to hear or play—No, not that, this—he could accommodate, normally.

The sound engineers you work with, do they typically end up contributing to the writing of the songs?

MR: I don’t think in any case. I think in Painter’s Joy there might have been one line that wasn’t working where John suggested another line, and I said, “You’re not getting co-writing credit on this, but it does work.” [laughing] I would have if he asked me, but he didn’t ask. I guess, in a collaborative sense, I respect John in terms of sonics. Maybe not in his view toward how something sounds, but the most semantical thing he ever taught me as an engineer was Watch your levels! Watch your levels! That way you’re not peaking or distorting, although distorting can be used in your favor sometimes. But I don’t think I’ve ever collaborated with anyone in this way before Malcolm. I very much consider his input a collaboration because his approaches I would have never thought of. He does a lot of orchestral writing. The opening song on the Seaworthy album is a song called “Arcadian Evening” and it has very symphonic, orchestral plucking and things like that that I wouldn’t have thought to use.

So will this new album be a departure from your earlier music?

MR: Probably closer to A Desire for Forgetfulness… There are 13 songs on the album, and there are 11 with vocals.

Ah, a pop album.

MR: I don’t know if it’s pop, but I find this stuff is pleasant to listen to, and I don’t even like to listen to my stuff. So I think the songs are at least palpable, and the recordings are really good.

You don’t like listening to your own music?

MR: It’s like being present at your own funeral, I guess. I mean I have to, now, because I’m rehearsing some of this stuff, but some of it [that] you haven’t heard for many years, like the Painter’s Joy album—I had not listened to it probably since it was released, or a little after it was released. Rehearsing it, I have to hear it more now.

I also did a duet with a gifted singer on the new album. I would consider that a collaboration. Her name is Mara Miller. She’s got a few recordings out on her own—I think she may have a bandcamp page. She’s got a beautiful voice; the local press had written up a review of her latest recording, or at the time it was her latest recording, and I listened to it and her voice just captured me.

So there’s a duet on the album; she echoes some of what I sing. I guess I would call it a duet, but not in the old fashion [sense], trading off lines, like Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton. But she did a wonderful job—for her sake and for her gift I look forward to people hearing that. It was an interesting thing because I gave her the demo with just me singing and I told her that I’m really open to any ideas that she had. There was a part at the very end where I was expecting her to sing, but she kind of delayed it a little, almost like a counter song in the way that she sang it. Very inventive—I wouldn’t have thought to do it. For singers I guess it may be something that comes more naturally, but I was really surprised by it. That was her input, and I think it really helped the recording.

I can’t wait to hear it. You know, “Saints and Sages” is a tidy way of summing up your music, which has always been steeped in religious and literary allusion. You grew up Catholic and converted to Protestantism, yes? Do you incorporate musical structures of hymn or prayer into your music, or is it more of a lyrical and thematic influence?

MR: I think hymns appeal to me greatly, melodically, and can still produce tears. Even hymns that I’ve heard for many, many years in the Catholic Church or the Protestant Church—both have just astounding melodies available. So I appreciate that, and if it’s absorbed in some way, I certainly acknowledge that that is possible.

There’s one song that I produced, kind of by accident, I think it’s on Few Traces: “The Mirror at St. Andrews.” I had a limited palette with the keyboard that I began with, but I had pictured cornets and horns. That probably wasn’t intended to be hymn-like, because a lot of this is just serendipity—I had a very short loan of this keyboard, and I had to come up with a lot of music in a short period of time, so it was kind of serendipitously arrived at. But that comes to mind. I’m not sure if there’s anything else that would be mathematically comparable to a hymn in terms of a repeated chorus or something like that. It wouldn’t be conscious.

There’s a Scottish 19th-, 20th century preacher and hymn writer named Horatius Bonar that wrote a few hymns, and I put one of his hymns to a folk melody, just to try it out. It’s not going to make Seaworthy—it’s an extra cut right now. But I was experimenting with that, and I just started augmenting it so much, and now it’s at the point where I’m going to have to subtract and figure out how I’m going to arrange it. But that was something I directly tried.

I’m not sure if there’s anything I can think of on any of the other stuff, but it might be a combination of the palette I choose from. I like slow attack strings and long decay strings that give the effect or impression that you’re sitting in a large hall or church or something like that. I’m sure not sure if it adds to that.

It certainly does—that quality is certainly there. It doesn’t always feel like you’re sitting in a church, but there is a spiritual and transcendental quality to it, which is I think very much part of the appeal of your work. Do you find that the same literary and religious inspirations that appear in your music inspire your visual art, or do you treat them differently?

MR: Well, I’m not sure. There’s no polemic or theological point that I’m trying to make, in that sense. It’s not directly illustrated, but in the things that, in the Christian tradition, the things that are traditionally affirmed: the value of humanity, the sacredness of life itself and things like that, I would hope that those are things that may be detected, although it’s hard to say.

The compliment—or I would it consider it criticism—most recently is that my work is Dickensian. I guess the figures that are portrayed in a lot of the work remind people of that. I can definitely see it. I try to stay away from [dating elements]—you know, classic figurative paintings aren’t really dated by clothing or style. If you put an automobile, something like that, you’re definitely gluing it to a certain period of time. A lot of mine are agricultural workers, or people that I grew up with—it’s a terrain that I’m very familiar with. I would say those affirming elements of mankind and creation and things like that are probably tenable and detectable.

Do you feel that you are working in any sort of school or tradition? There are obviously elements of folk art, or even kind of a Soviet Realism-style portrayal of people and the glorification of labor.

MR: I rate the Expressionists very highly because, being a self-taught painter, obviously I’m not a purist in terms of rendering things near-image or photographic. I would say my favorite artist is from the most energetic and inspiring era of painting, for me: Käthe Kollwitz. She does a lot of Expressionistic wood prints and charcoal drawings. She lived through the end of the second World War... a large body of work, used pencil and charcoal. Her most successful medium in my estimation would be her prints.

I have a book of German expressionist prints. They’re phenomenal.

MR: I’m sure she’s in there. Also, from a woman’s point of view, she was years ahead. She was very intimidated by a colleague of hers named Ernst Barlach that is also one of my favorite Expressionist and print makers, and he was a sculptor as well. She felt intimidated by his work. Her journals are available, and it’s a very good read. I’m not sure how much of it survived—I remember it being pretty brief, but some of her journals and some of her letters are available.

The Expressionists are, I would say, inspiring, but I would hope that I develop my own approach. That can be good and bad at times, in that somebody's school might know a shortcut way of portraying something that I don’t. But the visceral part of that—sometimes to work on an eight-by-ten canvas, a small canvas like that, might take me a whole year or two years to finish. I don’t know if it’s me and my rate that I work at, but that’s my approach.

O Let Me Ne’er Forget

How much of your work do you share with other people, and is that important to you?

MR: I wasn’t always a big believer in social media or the whole Facebook thing. I now have a public page and I share things with that, and the comments and the emails that I have gotten from people have kind of validated that there is a reason for doing it. For some reason your motivation might be different—to try to sell work. I’m very fortunate that I don’t rely solely on the sale of my work to live, and I realize how rare that is, and I don’t have a negative approach toward that. I don’t think you’re a sellout because you sell work or your work becomes popular. I do think that I have the advantage, in the digital age, to have that, and if I can watch another painter work, or someone that I admire talk about his work, that’s inspiring to me.

There’s the old Cocteau quote—he said that his work “was not to be marveled at but believed.” To me, that’s a great quote—if someone finds an affinity with whatever you’re doing and that, I can see, sharing that is an important thing. The only good part about going to my own openings is that you get to hear things like that, and you get to converse with people like that.

It’s very, very hard for me, always has been, to take compliments. I would think most people are that way, you just don’t know what to do with it, and some people, it might inspire some people to continue. I’d much rather have a really good conversation about just about anything else.

I have one last question for you. You’ve had a long career, making art and music at your own pace. What do you still hope to accomplish?

MR: Hmm… I’m not sure. There are still places on the planet I would like to see and would like to visit. I guess the rewards to come might be in, musically, maybe collaborations of some sort or opportunities to maybe work outside of my normal comfort zones in terms of venues or type of work, or the challenges. I always enjoy when you’re given a theme and you have the freedom to compose something to your own specifications, but to thematically interpret that theme on your own—challenges like that. I guess I would look for, in the future, more collaborations and opportunities to collaborate. As I said, I’m solitary by nature and I think sometimes that can be to your own detriment. You need to get out and have iron sharpen iron with other painters, other musicians and people as such. My experience with the recent album reinforces that—it’s been a really good experience, and I’d look forward to it again.

Listen to the unreleased track “Arrival and Departure” and catch an exhibition and performance from Mark Renner July 5 at Big Medium’s Creative Standard gallery followed by a performance July 6 at Kinda Tropical with Future Museums, The Infinites, and Distant Future.

Interview by Sean Redmond.

Photography by Christiana Renner.