inside documenta 14, Athens

Associate editor Katie Lauren Bruton traveled to Athens, Greece, recently to attend this year’s documenta. The exhibition, which takes place every five years, is one of the art world’s most important international events. Traditionally held in Kassel, Germany, the exhibition was expanded to a two-city affair this year at the behest of Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk. Katie shares her first-hand experience of the tension behind the event and provides a glimpse into some of the artists turning heads at this year’s showing.

My marked-up guide to documenta 14 in Athens.

With “Crapamenta 14” tagged across Athens, there’s no mistaking the skepticism among some Athenians about the 14th edition of documenta. Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk’s proposal to bring the exhibition to Athens (under the concept of “Learning from Athens”) raised fears of cultural imperialism and commodification of the Greek economic crisis. Conscious of these criticisms, Szymczyk hoped to create an opportunity for a new Greek narrative to form. He conceived of the bi-city exhibition as a space for unlearning what we know, an open forum for “aneducation,” where education becomes a collective, empowering process rather than a readymade tool.

Yet, as a visitor, I initially felt more lost than empowered. Roaming around Athens with only a one-page guide to documenta’s 47 venues, I felt as if I were intentionally left directionless. Breaking away from typical museum pedagogy, almost no context is given to the works, and even the exhibition guards seemed reluctant to give too much information, perhaps fearful of breaching the line between informing and interpreting. The latter was left entirely to me.

On my first day in Athens, it seemed like documenta and the city had a common perplexing, curatorial concept. My first day in Athens, along with trying to navigate in a city that predated the grid system with a tiny map that listed only major street names in their Latin script, the metro and trams were only available from 11 am to 4 pm due to a major public transit strike. But I was determined to make use of this chunk of time (and avoid navigating the bus system). My first stop was Parko Eleftherias, where I wandered through the former military barracks, only to discover the venue would not open until 2 pm. In the meantime, I went to the EMST (The National Museum of Contemporary Art), housed in a transformed brewery founded by the son of a Bavarian engineer.

Lois Weinberger, Debris Field—Exploration into the Decrepit (2010-16)

Overwhelmed by the first exhibition room, which showcased a set of housing contracts (manifested in work I would stumble upon later), I moved on to Lois Weinberger’s Debris Field. Here, the tables and walls displayed found objects that he, in what seemed like an act of archaeology-cum-ethnology, had excavated from his parents’ farmhouse in Austria. After documenta closes, he plans to return all of the objects back to the house.

Cecilia Vicuña, Quipo Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) (2017), with partial installation view of Khvay Samnang’s Preah Kunlong (The way of the spirit) (2017)

Cecilia Vicuña’s Quipo Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) was one of only a few large-scale installations at documenta 14.

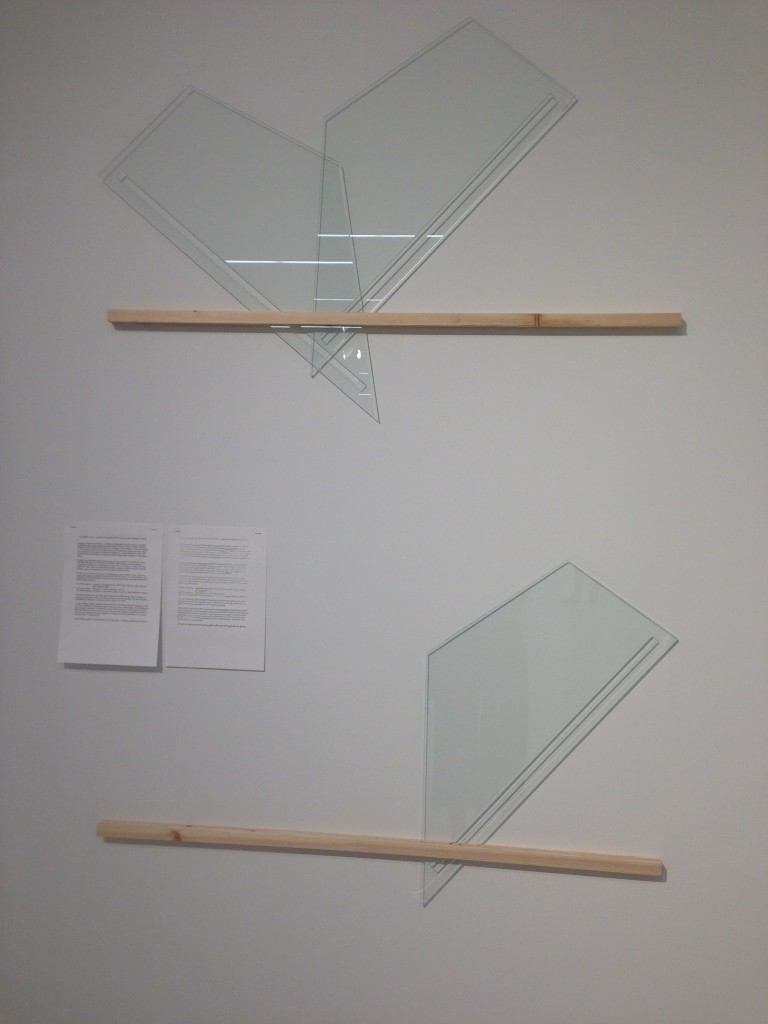

Yael Davids with André van Bergen, Score in Glass (2017)

In her installation Reading that Loves—A Physical Act, Yael Davis combined Mycenaen swords, a sculpture of the Roman empress Iulia Aquilia, the poet Else Lasker-Schüler’s death masks and compositions with armored glass from a factory in Kibbutz Tzuba, Israel, which designed safety glass for U.S. military use in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Synnøve Persen, Sámi Flag (1978)

Synnøve Persen designed the first (unofficial) Sámi flag in 1978, which was used by the indigenous Nordic people during the 1979 hunger strikes and demonstrations against a hydroelectric power plant in Norway. An official, and less politicized, flag was developed later.

***

My next stop was Parko Eleftherias (Freedom Park). Amid the more conventional institutions, the Athens Municipality Arts Center in the park was one of the most interesting locations: The site of the former military police headquarters and situated in front of the former torture and detention center, the building was later transformed into a gallery space.

Lala Meredith-Vula, Ferizaj, Kosovo, 28 June 1990_no. 14 (1990)

Lala Meredith-Vula’s photograph from the series Blood Memory was perhaps the most notable exhibition piece. The photograph documents a gathering in Kosovo, a disputed territory in the Balkan Peninsula. Another work was by architect Andreas Angelidakis, who removed parts of the Athens Municipality Arts Center building to expose the original structure and designed faux-concrete blocks that can be moved around to transform the space and provide seating for public events.

This venue also held one of documenta 14’s public programs, the Parliament of Bodies. In one specific project, I Owe You a Word, artists and participants were invited to donate a book to the Parliament of Bodies; the program was inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s suggestion that if the uses of Greek words were taxed, the country’s debt would be paid off in no time. The project is a collective gesture that questions the ownership of words and their ability to pay off a symbolic debt and outline a new social contract.

Video clips and books from I Owe You a Word, a project from the Parliament of Bodies in collaboration with Dimitris Athiridis and Theo Prodromidis.

Before the public transit closed, I left for the Benaki Museum. The strike turned out to include more than just public service employees, and as a result, the museum was closed. I still asked the security guard if I could see Hiwa K’s installation in the open courtyard.

Hiwa K, One Bedroom Apartment (2017)

A Dutch artist on vacation in Athens suggested I visit the Athens School of Fine Arts if I wanted to see the grimier, truer bits of the city. Typical of new sites of artistic action, the school is located in a former factory building.

Entrance to the Athens School of Fine Arts.

Many of the works at ASFA explore sites of learning and experimental education. Visitors could actually engage with these concepts in the old ASFA library, which served as the documenta 14 library and investigation space, open for visitors to read through the artist's materials and listen to the radio program Every Time A Ear di Soun.

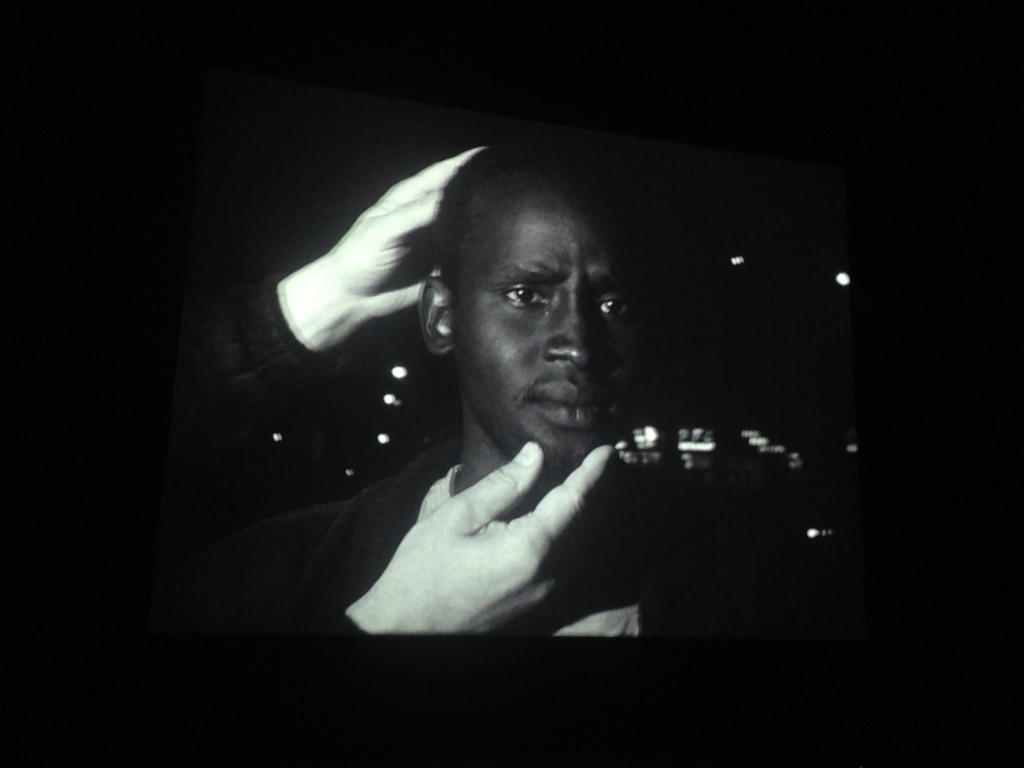

Artur Źmijewski, Glimpse (2016-17)

In what may have been the most brilliant piece at documenta 14, Artur Źmijewski’s Glimpse staged scenarios with refugees and migrants in Paris and the Calais Jungle. The politically charged film evoked a visceral reaction, it was so visually stunning.

Not far from ASFA, in a former print shop, is Otobong Nkanga’s soap production lab—the first phase of her project Carved to Flow—where soaps are created using butters and oils from regions in the Mediterranean, North and West Africa, and the Middle East. Arriving two hours too early for the next soap-making performance, only Otobong and exhibition guides were in the space, laughing about the rainy weather and asking if it ruined my plans to see “art.”

Otobong Nkanga, Carved to flow (2017)

Before heading to the Athens Conservatoire, I landed in Syntagma (Constitution) Square, an important space for political movements and demonstrations—hundreds were commemorating the Pontus Greek genocide in front of the Parliament building. Beyond the empty National Gardens and police-lined presidential mansion was the Conservatoire, a display of Greek modernity and the only completed structure from Bauhaus architect Ioannis Despotopoulus’s grand plan for the Athens Cultural Center.

Installation view at KSYME-CMRC.

documenta 14 partnered with the Athens-based Contemporary Music Research Center (KSYME-CMRC) to finally restore EMS Synthi 100, a rare analogue synthesizer from the 1970s. A placard invited visitors to try the “creature” out, with a warning that it may or may not respond.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e84fC8LY8II&feature=youtu.be Emeka Ogboh, The Way Earthly Things Are Going (2017)

In the Conservatoire’s stone arena was an installation by Emeka Ogboh featuring a traditional epirotic song paired with a real-time LED display of world stock indexes. On my way out, the exhibition guard stopped me, concerned that I didn’t listen at the base of the arena, clarifying that the artist had to install the nine “unwanted” speakers on the floor because of the poor acoustics. Each speaker represented a woman singing about her son leaving home. The financial crisis determines similar migrations today, she added.

Nothing caught my attention in the rest of the exhibition until I entered a room with tacky gold streamers—decoration for Theo Eshetu’s video installation Atlas Fractured, a collage of well-known visuals and sound clips.

Theo Eshetu, Atlas Fractured (2017)

Outside of the room were the following lines, taken from the the Seikilos epitaph, the oldest surviving complete musical composition:

“While you live, shine! Don’t suffer anything at all. Life exists but a short while, And time demands its toll.”

***

In the once vibrant, now largely deserted Kotzia Square is Rasheed Araeen’s Food for Thought: Thought for Change project. Under tents designed after Pakistani traditional wedding tents, Mediterranean food is cooked and served to groups of strangers for free, making for a coming-together of documenta 14-goers, homeless Athenians, and French tourists. It proved to entice more reflection than conversation when I sat next to three elderly Greeks. Glyka (sweets) turned out to be the only word we had in common.

Rasheed Araeen, Shamiyaana—Food for Thought: Thought for Change (2017)

On my final day, I went to see Rick Lowe’s Victoria Square Project in a northern area of Athens that travel guides typically warn against. When I walked into the shop-like space, a young urbanist was in the midst of presenting her findings on the high percentage of housing vacancies in Athens. In Victoria, one of the neighborhoods she surveyed, one narrative circulating among residents is that this neighborhood, once the backdrop for Greek cinema and more recently a home to makeshift refugee camps and immigrant groups, has lost its former bourgeois charm.

Rick Lowe, Victoria Square Project (2017-18)

In a neighborhood of parallel societies and diverse stories, Lowe designed the space as a meeting place/open studio for residents and small businesses to utilize and interact in. This “social-practice art” project, which also includes a print publication and networking strategies, seemed to be the first work carefully thought out for Athenians and possibly the only one to have an impact post-documenta.

The urbanist, who unsurprisingly hadn’t seen much of documenta 14 (this seemed to be the case for most Athenians), suggested I see a work by Maria Eichhorn at Amerikis Square—“for someone viewing Athens as an outsider, she completely gets what’s going on here,” she explained.

I didn’t need to ask anything further, so I followed my map to venue #40. What I found was a beautiful apartment buildingwith a sticker reading kunst on the door and locked with a bicycle chain.

Maria Eichhorn, Building as unknown property (2017)

Only later did I realize that the very last project I would see at documenta 14 in Athens was also the first—the contracts at EMST pertaining to this building, now an unowned property, protected against gentrification, speculation, and commercial acquisition. The need to both unlearn and learn from Athens finally seemed about right.

And yet, what Eichhorn perhaps understood best was that a short-lived exhibition wouldn't accomplish this. What remains after documenta 14 packs up and leaves Athens—when Airbnbs and apartments are once again vacant, when international audiences move on to Kassel, and when the art crowd returns to their cozy institutions? What happens after all of it is reduced to a catalogue, orsome write-up and a few images?

documenta takes place in Athens until July 16 and in Kassel until September 17.